How do HIV patients survive it?

A small number of people have been cured of HIV, but scientists are working on creating treatments that will be accessible to more infected people.

Over the past twenty years, Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infections have been treated by aggressive medical procedures to a handful of individuals. Several others have also received this treatment and appear to be HIV-free, but it is too early to declare them cured. Currently, their condition is considered a long-term remission, but they are considered potential treatments. All these patients received stem cell transplants. To treat these individuals, cells collected from adult bone marrow or umbilical cord blood donors were used.

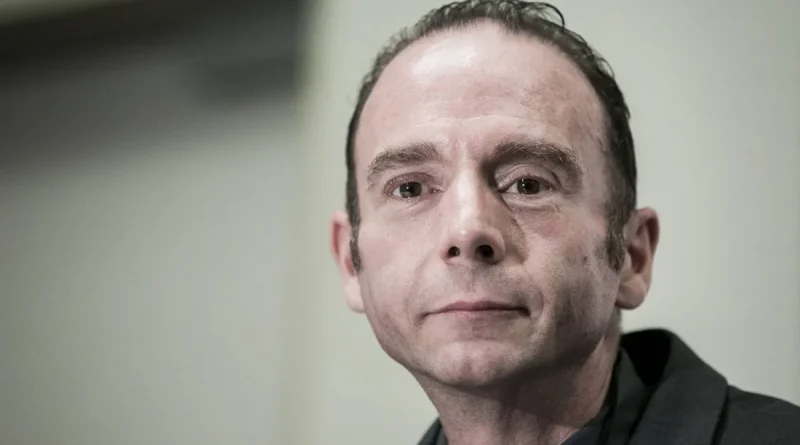

Timothy Ray Brown, known as the ‘Berlin Patient’, was the first person to be cured of HIV infection.

According to Live Science, scientists announced the first definitive cure for HIV in 2008 and since then two more definitive cures and two probable cures have been reported. The latest reports of such cases (one definitive cure and one probable cure) were announced in early 2023.

With the increase in scientific knowledge, these treatments may become more common in the coming years. Although currently these treatments are dangerous and largely inaccessible to the tens of millions of people worldwide who are infected with HIV.

HIV drugs, known as antiretroviral therapies (ARTs), can extend the lifespan of HIV-positive individuals and greatly reduce the risk of virus transmission, but these drugs must be taken daily throughout life, can interact with other drugs, and come with some risk of serious side effects. Therefore, scientists hope that these definitive cures will pave the way for new and more accessible treatment strategies that will save more people from the virus. What we know about the definitive cure for HIV is described below.

What treatments can definitively cure HIV?

All individuals who have definitely been rescued from HIV have been treated with stem cell transplantation. All of these patients, in addition to being HIV positive, had some form of cancer (acute myeloid leukemia or Hodgkin’s lymphoma). These cancers affect white blood cells, which are a key component of the immune system. These types of cancer are treatable with stem cell transplantation.

To simultaneously treat cancer and HIV, doctors collected stem cells from individuals who had two copies of a rare genetic mutation (CCR5 delta 32). This mutation deactivates a protein called CCR5 on the surface of the cell. Many strains of HIV use the aforementioned protein to enter cells.

The virus carries out its work by adhering to another surface protein and changing shape, and then attaches to CCR5 to penetrate the cell. Without CCR5, the virus cannot enter the cell (according to a review study published in Frontiers in Immunology in 2021, some less common strains of HIV use a different surface protein called CXCR4, and some strains can use both. Therefore, before transplantation, patients were screened to ensure that most or all of the viruses in their bodies used CCR5).

To prepare for a transplant, patients undergoing chemotherapy or radiation therapy are placed to eliminate cancerous and susceptible T cells (a type of immune cell) to HIV in their body. This weakens the patients’ immune system until the transplanted stem cells can produce new, resistant immune cells against HIV. Patients take immunosuppressive drugs for a while after the transplant to avoid graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). In GVHD, the immune cells derived from the donor attack the host body.

Most patients received stem cells taken from adult donors’ bone marrow. These cells must have high compatibility, meaning both the donor and recipient must have particular proteins called HLA in their body tissues. HLA incompatibility can lead to catastrophic immune responses.

One of the patients (the first woman to receive a stem cell transplant and is in long-term remission), received stem cells from umbilical cord blood donated at the time of birth. These immature cells are easier to match with the recipient’s body, so only a little compatibility is necessary. She also received stem cells from one of her adult relatives to help boost her immune system as the cord blood cells grew in number.

Since cord blood stem cells do not require a perfect match and are more readily available from bone marrow, such links could be offered to more patients in the future. However, according to Dr. Ivan Bernstein, director of the Los Angeles-Brazil AIDS Consortium at the University of California and one of the treated patients, HIV-positive patients should not be at high risk unless they have another disease that requires stem cell transplantation.

Who was the first person to be cured of HIV infection?

The first person to be treated with HIV was initially called the âBerlin patientâ because he was treated in Berlin, Germany. He revealed his identity in 2010.

Timothy Ray Brown, an American, was diagnosed with HIV while studying at a university in Berlin in 1995 and started taking ART drugs to reduce the amount of HIV in his body. In 2006, Brown was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia and received radiation therapy and bone marrow transplantation in 2007 to treat the disease. Brown’s doctor saw this as an opportunity to simultaneously treat his patient’s leukemia and HIV.

On July 24, 2012 in Washington, Timothy Ray Brown held a press conference to announce the launch of the Timothy Ray Brown Foundation.

After radiation therapy and an HIV-free transplant, Brown’s cancer returned and in 2008 he needed a second transplant. That year, researchers announced that the Berlin patient was the first person to be definitively cured of HIV. Brown remained HIV-free until the end of his life. He passed away in 2020 at the age of 54 after a relapse of leukemia and cancer that spread to his spine and brain.

How many people have been cured of HIV to date?

As of March 2023, three people have been cured of HIV and two are in long-term remission. In addition to Timothy Ray Brown, cured individuals include the London patient (named Adam Castillejo) and the person from Dusseldorf whose name has not been disclosed. The two probable cases of cured individuals include the man known as the Berlin patient and the New York patient. The New York patient is the first woman to receive the treatment.

Dr. Deborah Persaud, who oversaw the New York patient and is the interim director of the pediatric infectious diseases division at Johns Hopkins University, said at a press conference held in March 2023 that there is currently no formal distinction between HIV treatment and long-term remission.

Dr. Steven Deeks, an HIV specialist and professor at the University of California, San Francisco, who did not participate in the patient’s treatment, said “The Dusseldorf patient was probably the second person cured, but the medical team was cautious and stopped antiretroviral therapies after several years and waited a long time to conclude that he had been cured. ”

The patient of Dusseldorf was treated in 2013 and continued taking ART drugs for about six years and has now been off medication for over four years. Meanwhile, in 2016, Kastykhu received a transplant, stopped ART treatments just over a year later, and prior to Dusseldorf, his treatment was confirmed in 2020.

What can be learned from treated HIV cases?

Treated cases provide insights into how the body changes after transplantation and also provide insights into future strategies for HIV treatment.

Scientists have found that even after transplantation, very sensitive tests show scattered effects of HIV DNA and RNA. Although, according to Dr. Björn-Erik Olejniksen, senior physician at the University Hospital Dusseldorf, who performed comprehensive tests on remains of HIV virus in the Dusseldorf patient, these viral remnants are unable to replicate. He told Live Science none of these viral effects are capable of replication. Physicians involved in other treatment cases also performed similar tests and reached the same result.

According to Johnson, changing the immune system may be a better benchmark for measuring transplant performance. About two years after the transplant, the Dusseldorf patient had immune cells that responded to proteins related to HIV, indicating that the cells had encountered the virus and stored a memory of it. Johnson said: ‘But over time, these responses disappeared, until the HIV reservoir reached zero. Changes in immune activity were a convincing sign that the Dusseldorf patient could stop ART treatment.’

Are scientists conducting research to find other ways to treat HIV?

According to Johnson, scientists are working on alternative treatments that can cause these changes in the body without relying on donor stem cells. By avoiding stem cell transplantation, future treatments may eliminate the need for intense chemotherapy and radiotherapy, as well as the use of immunosuppressive drugs and the risk of GVHD.

Some research groups are developing HIV treatments based on modified cancer treatments, in which some of the patient’s immune cells are taken, the CCR5 receptor is removed, and the cells are made responsive to HIV proteins before returning to the patient’s body.

Potential therapeutic strategies also include gene therapies that edit DNA cells of the body to delete the CCR5 encoding gene or make cells produce proteins that inhibit or inactivate CCR5. Some researchers are also working on methods of targeting CXCR4. Dix stated, ‘Given the gene editing revolution happening in other medical arenas, it may eventually be possible to do this with a single injection.’ Johnson noted that these approaches are still in the laboratory and being tested on animals, so scientists do not yet know how they will work in humans, though he sees reason for hope.